Bryntail – Central Grammar School’s Welsh Camp

Central Grammar School’s Bryntail Camp origins date back to before World War One

Inspired by a visit to Birmingham in 1908 of General Baden-Powell (the founder of Scouting), a Teacher in Suffolk Street – Herr Seckler, with help from Monsieur H. Guerra(another Cental Master) established tented school camps at Holt Fleet in the Severn Valley. When, during the war camping there became impossible, the school camp was transferred to the small cottage of a friend on the top of a mountain on the east side of the Plynlimon range in Wales – BRYNTAIL.

It was here that, from 1915 onwards, school camps were organized Monsieur H. Guerra, whose many interests which benefited the school also included theatricals, rugger and swimming. These two masters, Herr Seckler and Monsieur Guerra, established the very English traditions of our Welsh camp – traditions which continue and grow to this day. It is impossible to overstress the importance of Bryntail to Central – in the eyes of many old boys it is Bryntail that enshrines the Central tradition, infinitely more than the (then 1960/70s) elegant modern school building in its un-central position at Tile Cross.

The following article was written by Bryntailer – Richard Fryer – Old Central 1957-1964

The Bryntail Story – Background

The following began as an article for “Pen Cambria”, the local history magazine for Mid-Wales. The new edition is always sold from the steps of Llanidloes Town Hall on Charter Market Saturdays. They seemed to like it and it was published in the Spring edition of 2015 to coincide with the Bryntail Centenary. The information (and many of the words!) came from articles written by Henri Guerra and Jim May that were published in “The Hammer”, the magazine of the Central Grammar School, from camp log-books, from a recorded conversation between Harry Walker, Brian Hutton and Don Abbey, from talking to P.J. Smith and Eric Sant and from my own nerdish store of Bryntail folklore. I have added to the original article, I may add to it further in future years, but perhaps I should get out more………………

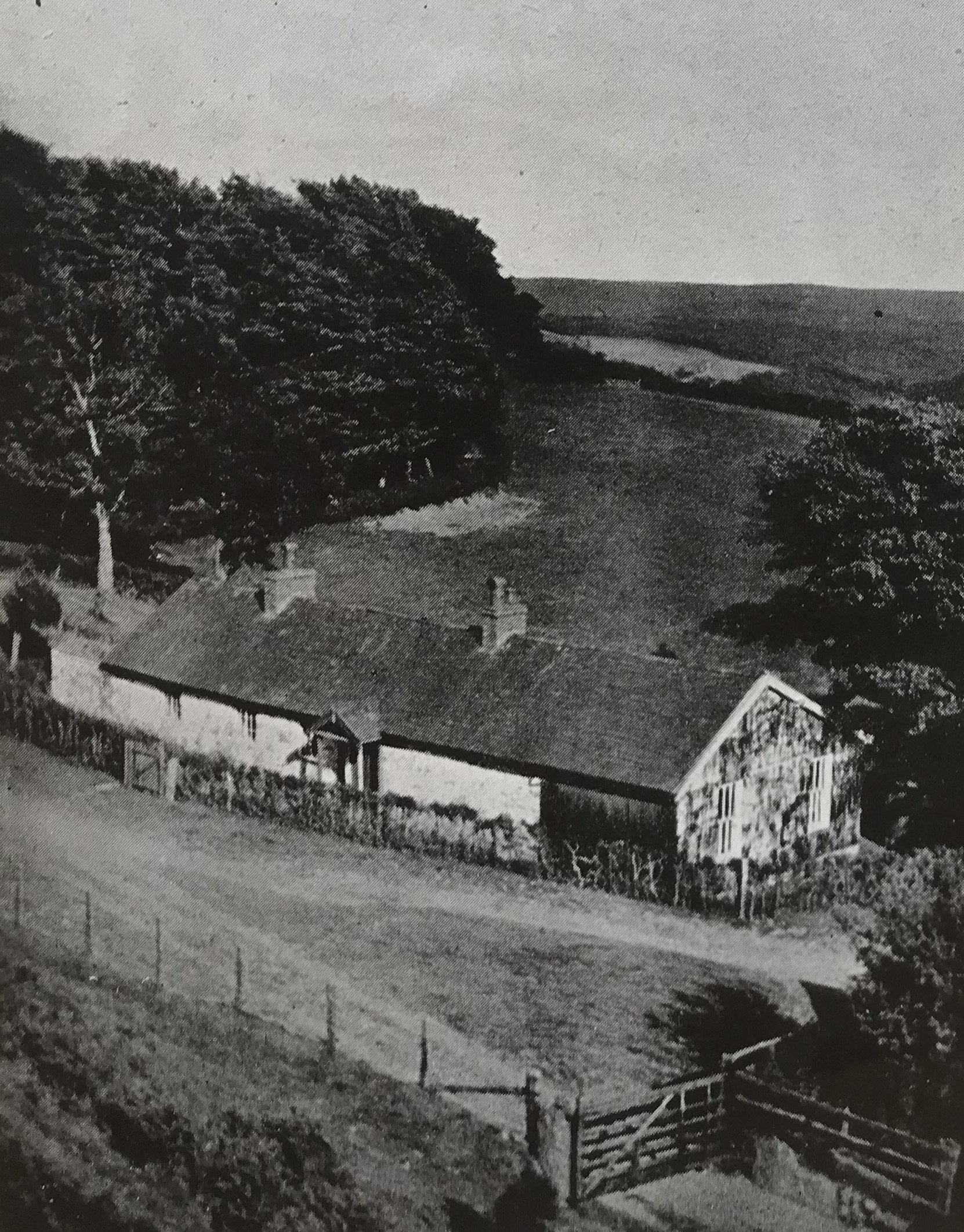

Bryntail Cottage

If you walk along Glyndwr’s Way north from Llanidloes you will eventually leave the B4196 and walk along a flat metalled road heading towards Bryntail Farm. You will skirt the farmyard and pass behind some barns, ancient and modern. The path then leads on through a small copse and through a gate onto the track leading to the Clywedog Dam. Just through the gate down the bank to your left is a low single storey slate roofed cottage in a small hedged garden. Many people pause just beyond the cottage where there is a bench on a mound overlooking an old spoil heap.

Nowadays this is a peaceful place, a perfect spot to open the flask and sandwich box and sit for a while to take in the view. Behind you is a group of old stone buildings, to your right a rather nondescript portacabin but before you a beautiful Mid-Welsh patchwork of soft green hedges and fields looking over the Clywedog Valley to the Severn Valley beyond. Had you been here 150 years ago, however, it would have been a very different scene.

The peace would have been broken by the sounds of mining. The view might well have been obscured by the smoke from an engine working in the building down the slope to your left. It would have been pumping water and lifting men and materials from Gundry’s shaft which remains in the copse next to the ruin. There would have been another shaft on the hill behind you, another in the farmyard now covered with a barn, yet another just beyond the farm and several more along the road you have just walked.

All of this activity was to extract the lead ore from the lode which ran from the slopes of Plynlimon, across the Severn and Clywedog Valleys and on to Van where the greatest amount was extracted at the great Van Consoles Mine. Bryntail ore was sent down a track down the slope to a lower dressing floor by the river. More ore was processed in the buildings you will see as ruins as you walk on by the Clywedog Dam. Bryntail Cottage was the hub of the operation being the mine captain’s cottage and offices of the company.

Van Consoles Mine

The full story of the Bryntail Mine operation merits a separate article. I would like to tell you what happened when the price of lead crashed; the miners left and a link was forged between a school in Birmingham and Bryntail Cottage which has continued unbroken for nearly 100 years.

Central Secondary School was founded in Birmingham in the late 1890’s. It was established to educate boys in technical skills to go on to take up apprenticeships or go on to further education to work in the local engineering and manufacturing trades. It was, indeed “central”, being in Suffolk Street in the City Centre.

From the outset, it seemed to attract an international staff. One of these was a Mr Seckler, a German national who joined the school in 1901. In 1908, he organised a camp for 32 boys at Holt Fleet in Worcestershire. It appears that most of the boys walked from Selly Oak tram terminus to the camp site (not a short stroll!), where they stayed under canvas for two weeks. Later they travelled by train to Stourport, then by river steamer to Holt Fleet.

This was fortunate, as one essential piece of camping equipment was, evidently, a harmonium! In 1910 Mr Seckler was assisted at camp by a young Parisian, Henri Guerra, (reputedly from an aristocratic family and educated at Harvard) who had joined the school that year to teach French. Guerra continued to assist, and they were away at camp when World War One was declared. Seckler was rewarded for all his efforts by promptly being interned. He was suspected of communicating with the enemy by means of a kite. It turned out that it was one of his pupils that was an expert kite flyer, not he! Another version has it that he was accused of laying concrete bases for heavy guns to demolish the University buildings at Edgbaston. He was in fact, overseeing the foundations for a new pavilion at the school’s sports field in Harborne. A project for which he had done the bulk of the fund raising!

Guerra was his obvious successor, but his challenge was to find a new site for the camp the Holte Fleet site having been requisitioned by the Army. A friend of Guerra’s, his Doctor in Birmingham, Dr. Roberts, suggested he might let a small cottage he owned “On top of a mountain on the east side of the Plynlimon range”. This seemed a good suggestion so, in his own words, Guerra “Immediately took train and taking three boys with me explored the possibilities. I decided on the spot that Bryntail was to be the future camping ground of the C.S.S.”

The first camp took place in the summer of 1915. It lasted for a month with twelve boys attending for the first fortnight; seven of whom stayed on to join the campers of the next fortnight. The difficulty of organising such a venture in those days in such a remote location in wartime can only be imagined. An Old Central, Harry Walker, attended this first camp run by Guerra at Easter in 1915 and recorded his recollections. He talks of sleeping on the floor of the cottage on old wheat sacks filled with straw from the farm. Cooking was done over a fire fuelled by wood brought from nearby Gelli wood. Basic food supplies were bought from Francis the grocers in Llanidloes and collected by horse and cart from the farm. The menu was basic, to say the least. Porridge for breakfast, corn beef hash followed by rice enlivened with prunes or dried fruit for lunch, jam and bread for tea and shredded wheat for supper (a menu which had changed little when I attended my first camp in 1959!)

Cooking temperatures were not easily controlled over damp wood and food was often late, charred or both. Sanitary arrangements were also very basic, with one earth closet serving the needs of all campers. Harry recalls that at the end of a camp “the six-foot drop”, as it was known, was “ripe for improvement!” Not that all this did Harry much harm. He became a head teacher in Birmingham and worked as a swimming commentator for the B.B.C. He died in 1998 aged 103, having had a lifelong love of Bryntail Cottage and its surroundings.

And so, the pattern was set. Camps were held at Easter and during the summer, and these Guerra camps were held until 1928. The programme was decided by “H.G.”, printed beforehand and carried out regardless, of weather conditions. It crammed a great deal into the time. There was daily bathing in the icy Clywedog, four paper chases, four despatch runs, two Sports Days, two Gymkhanas, tugs of war, hill climbing and competitions, swimming sports, one junior sports day, two mock trials and four concerts which were attended by guests from neighbouring farms. In addition, there were four long walks and baseball every evening after tea. All this provided on a very small charge, 12/6 to 14/6 in 1919. This included the train fare (Snow Hill to Shrewsbury, Shrewsbury to Moat Lane, Moat Lane to Llanidloes, then the three mile walk to the cottage). This remained the route to Bryntail until the ravages of Dr. Beeching in the 1960’s meant that a coach had to be hired.

Gales weren’t the only problem that the camp faced in 1928. Henri Guerra was on sick leave and this led to his retirement in December of that year. He and his twin brother, Renee, decided to spend their retirement in the town where they had built up so many connections and friendships. Their life in Llanidloes deserves yet another article. They threw themselves wholeheartedly into community life. Henri ran a boy’s club in the old flannel mill by the Short Bridge (now converted to flats). Renee was appointed as Billeting Officer for evacuees arriving from all over the country, safeguarding their safety and welfare. Later he worked as curator of the Town Museum which was then housed in the Old Market Hall. They are still spoken of with respect and fondness in the town, indeed, to this day posies of flowers regularly appear on their grave in Dol-Hafren cemetery on the anniversaries of their deaths.

So, in 1928, Bryntail had no leader, only one good tent, and beams supporting the roof of the Miner’s Cottage were on the point of collapse, and there were no funds. However, the “Bryntail Spirit” engendered by the cottage and its activities shone through and, faced with the prospect of losing the place, masters and boys, Old Boys and parents worked together to raise money and make the necessary repairs so that camps could continue.

Two new leaders also came forward: P. J. Humphreys and Norman Loveridge. Both had been appointed in the 1900’s and both went on to teach at the school for over 30 years. Both had also served in the Great War which probably explains the military way in which their camps were organised, Humphreys taking the role of Quartermaster, whilst Loveridge was Officer-in-Charge.

Under their stewardship, the camp evolved. The fixed programme was abandoned and activities decided daily so that weather conditions could be considered. The basic activities remained much the same, however, the “wide” games (Paper chases, dispatch runs and Prisoner’s Release) continued, as did swimming, baseball and the “Two-Mile” Relay. Walks became more frequent and longer, visiting Llyn-Ebyr, Craig-y-Llo, Pennant Falls and Marshes Pool, as well as climbing Bryntail Hill, Pen-y-Gaer and Van

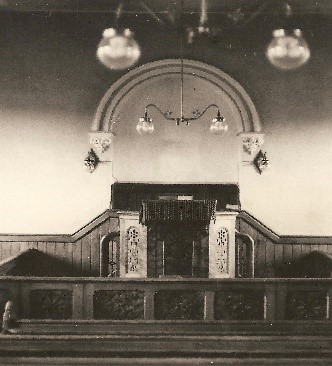

Another Guerra Institution retained was the visit to Deildre Chapel. One Sunday each camp, after much boot polishing and clothes brushing, the whole camp would walk down to cross the river by the old, swaying Miner’s Bridge and climb the steep path up Pen-y-Gaer to the tiny chapel, seemingly in the middle of nowhere. The boys waited on the bank outside as the local people walked the muddy tracks and paths from their farms and arrived to take their seats. It was sometimes difficult to find a preacher who could take the whole service in English which to some of whom was almost a foreign language. It was equally difficult to coax the harmonium into life after standing through a cold damp winter, but despite all this the boys were generally enthralled (or petrified) by the fervour of the preaching and strove manfully to sing the old favourite hymns, even though pitched an octave higher than comfortable. They filed out still pondering the exhortation to “raise one’s Ebenezer”. The return journey was somewhat quicker as it was traditional to slide down the slope to the river using a waterproof as a sledge. On a damp Sunday, this could be surprisingly quick and quite bruising descent! Only once did this lead to serious injury when a slider veered off course, over some rocks and landed in a heap on the lower path. A stretcher journey up the path to the cottage was followed by a trip to Aberystwyth Hospital, a long journey before air ambulances. Thankfully, the damage was repaired successfully and the injured party still visits the cottage some 60 years later. Chapel visits continued until Deildre closed in the late sixties. Then a longer walk was involved over to the palatial (by comparison), Old Hall Chapel in the Severn Valley.

Deildre Chapel

Work on the cottage progressed. The Miner’s Cottage was repaired and used as a recreation space and to everyone’s relief (!) new earth closets were constructed. These were regularly limed and a local man with a (very) long handled shovel was employed to dig them out each autumn. His rhubarb was renowned locally!

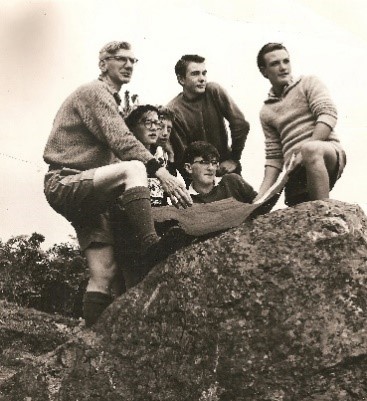

Much of this work was carried out by ex-pupils of the school. As in Guerra’s time, these “Old-Boys” arrived at camp in substantial numbers. They came in cars, on motorbikes and cycles, hitch-hiked; one was reputed to have walked from Birmingham! They were rewarded for their efforts in building, painting, chopping and sawing, grass and hedge trimming with a bed in “The Dry”, a draughty shed behind the cottage, food and copious amounts of strong tea. Along with the older boys, they also formed teams which played the locals at cricket and rugby. The latter was played on the town football pitch with long poles tied to the goalposts for conversions. Such fixtures continued well into the 1960’s and led to many social contacts being made in the pubs of Llanidloes and at the local dances. At least one old boy married a Llanidloes girl and there were several near misses!

The Arnie Faulkner Years

However, the gathering crisis of 1939 meant that the summer’s camp was the last for seven years and, as it turned out, the last of the Loveridge era. The school was partly evacuated to South Wales, the remainder moved to King Edward’s in Aston. The cottage was left cold and deserted for the duration.

It was 1947 before thoughts turned to re-opening. The school itself was, however, facing a crisis at the time. It was now a grammar school, but had been re-housed in cramped and unsuitable buildings in Bordesley Green, flanked by railways and evil-smelling factories. It was low on numbers and short of funds. Norman Loveridge, by this time Deputy Head, decided not to open Bryntail again but to hand it on.

Arnold Faulkner (EAF) had joined the school in 1946 to teach Physics, or rather he had re-joined it for he was an Old Central and, indeed, had been a regular Bryntailer since 1927. He knew the place, its activities and traditions like few others. Add to these virtues, a sound practical knowledge, a very persuasive nature and the patience of a saint, and there could have been no better choice to take on the challenge.

And what a challenge! The cottage itself had survived the years of neglect quite well; though only one steel tent was still intact, another badly damaged and the third a battered heap of scrap iron. Worse was the challenge of rationing, which affected every form of food, fuel or clothing. Even bread, that staple of the camp diet, was in short supply and could only be bought by giving up “Bread Units”. Undaunted, Faulkner (as he was known to the Evans of Bryntail Farm and many others locally), re-opened the cottage with 14 boys in 1947. They slept in the cottage and in the one good tent and, two by two, took it in turns to cook. An experiment never to be repeated!

So, began thirty years of steady development under Arnie’s stewardship. He was ably supported by many other members of staff, but most regularly and most notably by Jim May, French Teacher and later Deputy Head at the school. Contrasting with Arnie in so many ways, fiery while Arnie was cool, scholarly while Arnie was practical, voluble while Arnie was quiet, a pipe smoker while Arnie preferred Players, they made up an unlikely but effective partnership. It was largely Jim who recorded every detail of camp life in the Bryntail Log Books or “Llyfr Coch Bryntail” as he called them. They reflect his many interests and record many items of local and natural history, local gossip and folklore, as well as all walk routes and the results of all games. They are still pored over at reunions.

Jim May (Left)

1947 Campers

The log entry for Easter 1950 records what must have been the greatest feat of Bryntail construction and engineering ever achieved. Accommodation at the cottage was a problem when it re-opened. One tent was salvaged from the wrecks, but with camps becoming more popular, extra space was needed. An Old Boy and Bryntailler, Charles Tracey, was a pilot who was killed in the Second World War. His mother made a gift to Bryntail in his memory and this formed the basis of a fund which was used to purchase a redundant Nissen hut; found in Cumberland in answer to an advert in “Farmer’s Weekly (cost 18’2d), it was transported to Mid-Wales as one hundred or so rather battered and dirty corrugated iron sheets, metal ribs and wooden end pieces. It cost £56. Easter Camp of 1950 was mainly devoted to the erection of this hut, which would enable 20 or so boys to sleep, in beds, on a concrete floor in relative comfort.

It took a group of masters, older boys and old boys of that camp to level the site (where the portacabin stands today), dig foundation trenches and put in hardcore before mixing (by hand), and laying several tons of concrete for the hut floor. They laboured in atrocious weather, snow and hail, with winds blowing down from Plynlimon with such force they blew the concrete off the shovel before it could be laid, and tore sheets of corrugate iron from the grasps of several men and sent them sailing through the air towards the river. Two of the party went down with tonsillitis, with one hallucinating and registering a temperature of 101.6 before Doctor Davies (Llanidloes) was called.

They succeeded, however, in preparing the site, and the considerable work of putting the hut together was completed during the Summer Camp of that year. It was a major piece of construction, admired for miles around. It is recorded in the Log that the work was inspected most evenings by the Evans brothers from the farm, either by vigorous prodding with a walking stick or by being grasped with powerful hands and shaken violently to see if anything would fall. It is also recorded that nothing did.

The “Tracey Memorial Hut” saw service for the next twenty years with all spaces full as camp gained in popularity. A luxurious addition to the hut was a cast iron stove which, if stoked illicitly after lights out, could be made to glow cherry red and light the equally illicit Woodbine.

The camp thrived in the 50’s and early 60’s, as did the school. It moved to new premises on the very outskirts of Birmingham in Tile Cross in 1957, and there was an influx of young, actively involved staff, some of whom were supporters of Bryntail. They, along with older regular supporters, and the ever-present Old Boys, provided E.A.F. with valuable help with activities and repairs and maintenance during these years, but no one could predict what lay ahead.

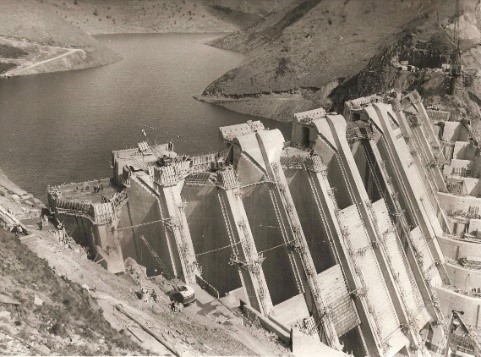

Llynn Clywedog

In the late 50’s rumours began to circulate of a plan to construct a dam somewhere in the head waters of the Severn to relieve and control flooding in the Upper Severn Valley. After discussion, it was proposed that the narrow valley of the Clywedog at the base of Bryntail would be the ideal spot, broadly at the site of the camp’s bathing pool!

The City of Birmingham was prime mover in the scheme as, not only would it control flooding, it would also enable water extraction downstream during the drier summer months. Arnold Faulkner gathered support among pupils, ex-pupils and their friends and families and gathered signatures on a petition objecting to the scheme. Sufficient were gathered to force a Public Meeting at the Town Hall and a Town Poll to be held. The objection was heavily defeated and Arnold made few friends among the City Council. He did, however, enlist the support of Emlyn (later Lord) Hooson, the local M.P. who could influence the drafting of the Parliamentary Bill, which enabled the scheme, and significant changes were made to details of road making, quarrying, and landscaping. Most significant, however, was the limitation of the recreational uses of the lake to angling and sailing, with the only powered boat allowed being the sailing club rescue boat. Llyn Clywedog might well have been a much noisier and smellier place but for the efforts of Arnold Faulkner.

Exploration began in 1963 with core drilling at various sites and rain gauges placed on the hillside. The scientists might well have wondered how these filled to the brim overnight when the camp was occupied, and why rain was yellow in Mid-Wales! A hutted workers’ camp was placed on the rugby touch and baseball field, old tracks became roads, huge lorries thundered around the valley and the mighty Clywedog was diverted through an undignified narrow metal tube, while thousands of tons of concrete were poured into what we had known for years as Hammer pool. The valley was filled with more people and activity than it had known since the Ice-Age.

As the dam rose and impounding began, large tracts of countryside were cut off, and many old walk routes were lost as river crossings were drowned and new tenants erected new fences without stiles. Camp adapted to the new conditions. Tents were bought for lightweight camping expeditions. Arnold was a founder member of the Sailing Club and funds were raised for a dinghy. A new trophy was designed to be awarded for most capsizes in an afternoon, but whatever new activities were introduced, it felt that the whole essence of the place had changed; we had lost our exclusive use of an area which, perhaps rather selfishly, we had regarded as our own for decades.

In 1968 Arnold Faulkner was about to leave the cottage at the end of a stay with his wife when he decided to cut the hedge. As he did so he began to feel unwell. He managed to drive home where it was discovered that he had suffered a serious heart attack. He made a partial recovery and returned to school and to Bryntail, but never to full good health. His last camp in charge was in Summer 1971. In June 1972, he suffered a fatal heart attack whilst undergoing heart surgery at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham. A month later his ashes were scattered on the summit of Bryntail among the gorse, bracken and springy turf of the place which had meant so much to him.

But the indomitable spirit of Bryntail lived on! Another Old Boy and Bryntailler, Peter Smith had been appointed to the School staff in 1971, as Librarian but his Bryntail connections were shrewdly noted by the then Head teacher. His first camp in charge was at Easter in 1972, by which time a committee had been formed to oversee the camp. It consisted of staff, Old Boys and members of the newly formed Parents’ Association. Several working camps were organised to maintain and repair buildings and fabric and the pattern of Easter and Summer camps continued, well supported by other staff and the usual contingent of Old Boys. Sailing became a regular activity and the school mini-bus was used to extend the scope of walks and expeditions. Camps generally had fewer numbers, but were run in a rather more relaxed way with fewer of the more demanding physical activities. The menu was certainly more varied with curry followed by Christmas pudding on offer on one occasion! Overtures were even made to M.A.N.W.E.B. to install electricity. Arnold Faulkner had made them remove the initial pole that they planted. He preferred the softer light of paraffin lamps!

Change Is In The Air

Greater change was, however, in the air. In 1974 Birmingham decided to close most of its Grammar Schools. Central was amalgamated with the neighbouring Byng Kendrick Girls’ Grammar School and reopened as a mixed Comprehensive, Byng Kendrick Central School. Also, Peter Smith was promoted to a nearby school and left.

Fortunately, two other teachers, Mick Jones and Eric Sant had become involved with the cottage, and were prepared to take on the considerable challenge of adapting and developing it to mixed camps. They wanted to see the cottage used on a more regular basis and to develop it more as an outdoor activity centre, integrating the activities into the school’s curriculum. They realised that they needed the support of the whole staff for this venture and consulted with them about what needed to change to gain it. Creature comforts were top of the list. The new management set about raising the money to fund the modernisation. Two hundred letters were written to local firms, a Summer Fair was held, local charities were contacted and a weekly lottery was run at the school. The money raised funded major improvements.

The New Toilet Block!

Electricity came marching across the hill on new poles and the cottage was wired for power and light. Lights-out was done at the flick of a switch rather than by collecting lamps. The miner’s cottage was re-floored and decorated as girls’ accommodation, the W.W.1 tents finally ending their days as scrap iron. The water supply, a spring shared by the farm and unreliable in summer was found to be too high in lead content. This meant a new supply, brought in by tanker, had to come from the other side of the valley. This, despite the availability of 11,000 million gallons (50,000 megalitres in new pennies) of the stuff just around the corner! A trench was dug to bury the pipe from the riverside, up the hill and along the path to feed into the cottage cistern. A distance of half a mile. A digger was employed only for the last 100 yards or so where it proved too rocky for spades and pickaxes! A septic tank could then be installed and a toilet block built with the unthinkable luxury of flushing toilets! With help from Severn Trent the cottage was re-roofed. All this was achieved by working parties of staff, pupils and parents who, under the direction of and often fed and watered by Eric Sant, devoted hours of time and hard labour to bring the cottage up-to-date.

Their efforts were rewarded by the support of the staff. The cottage was used throughout the year enabling pupils to visit Bryntail several times during their school career to study and enjoy the countryside, to be independent and enjoy each other’s company. This continued until the late 80’s, by which time both Eric and Mick had moved on and Peter Mann inherited the responsibility for Bryntail.

The Nissen hut was found to be leaking and judged beyond repair. It was demolished and new accommodation in the form of a portacabin was craned in on the Nissen base. Unfortunately, this proved to be even less water tight than the Nissen, and accommodation became limited to the Miner’s Cottage. Group sizes were then limited and this, combined with a period of work to rules and action by teachers, made it very difficult to arrange cottage visits. To add to the difficulty, the School underwent a drastic and tumultuous reorganisation, being combined with another failing local school, undergoing three changes of Head and Management in as many years, and incurring a huge financial deficit. Visits to a remote Welsh cottage were not a priority.

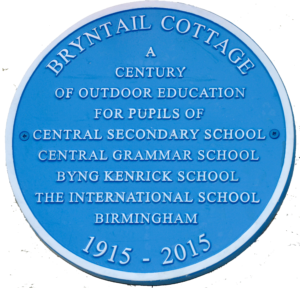

One positive development in this period was the institution of Annual Re-unions of past Bryntaillers at the cottage. Begun in 1997, the 100th Anniversary of the founding of the Central Secondary School, these have proved to very successful attracting around 50 former campers each year, often with wives and families. These events have also raised vital funds for the cottage as well as extra revenue for the pubs, B and B’s and restaurants of Llanidloes! In 2015, the centenary of the first use of the cottage, over 100 ex-campers, members of staff past and present, the Davies from the farm and other interested locals gathered at Bryntail to mark the occasion. Many tales were told, old friendships renewed, a whole hog was consumed, speeches were made and a plaque unveiled. There was even bunting!

So, sitting on your picnic bench, resting on the long trek along Glyndwr’s Way, you might well hear a ghostly whistle calling campers to a meal in the corrugated clad dining room, or catch an ethereal whiff of wood smoke from the fire cooking the corn beef stew, or catch a snatch of raucous singing from the direction of where the Nissen stood. The Cottage looks rather forlorn these days but its future is bright. Tile Cross Academy, who have inherited the legacy of Bryntail for the next generation, are in the process of establishing a Charitable Incorporated Organisation to take on the management and source funds for a complete refurbishment.

Hopefully the legacy of challenge, excitement, fun and friendship that it has generated for over a century will continue for another 100 years.